In the building where I spent my early years, Kismet Arcade in the heart of Durban's Casbah, lived Sita Dhupelia and her suave husband, Nanoo. Her children, Satish, Uma and Kirti were part of everyday life. In a city full of excitements, the Arcade developed a very particular mystique with the Lotus Club at the top of the building and a snooker club in the basement. We occupied the first floor flat with a little balcony. But you could never venture out onto it because people on the higher floors often offloaded their garbage or cigarette butts on to your head. But you could venture into Sita Dhupelia's flat for a warm welcome and always the offer of a cup of tea. But another fascination also motivated the visits.

"[N]ot many people get to hurry up three flights of stairs to take tea with someone in the direct bloodline of a saint."

My mum told me very early on that the man who adorned the wall in our lounge was Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, Sita's grandfather. Every now and then she would provide little snippets of Gandhi's life. It was she who told me about Churchill's remark about the half-naked fakir: this after I begged her to dispense with her sari and wear a skirt like the white ladies walking down West Street. She told me about Gandhi pouring his tea into a saucer in some well-heeled London gathering and earning the scornful question of an aristocrat: "Why do you slurp from a saucer?" to which Gandhi replied, "So I can share the cup with you."

To a boy of 8, these stories, told at the height of apartheid's arrogance that forced us to live in narrower and narrower corners of the city, and where even the best parts of the nearby ocean were reserved for Whites, captivated and frustrated me. I drew pictures in my head of this mountain of a man whose every action, every utterance, constituted for my mother such a dominating moral landmark. Imagine the awe in visiting the Dhupelia's then, for not many people get to hurry up three flights of stairs to take tea with someone in the direct bloodline of a saint.

Down the road was the Raj Cinema. Here John Wayne held sway. The matinee show was jam-packed with youngsters. We screamed warnings to John Wayne when the bad guy with braids crept up behind him and clapped and danced when the last Indian was shot in the middle of the forehead.

John Wayne and Mohandas Gandhi. These were my heroes.

One day I asked my mother, "When will I meet this Gandhi?"

"You will Ashy boy, you will."

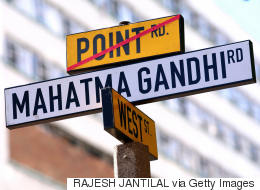

For seven years, on and off, Goolam Vahed and I have met Gandhi. In all kinds of places. In the archives. In journals and books. In newspapers and conferences. In monuments and street names.

"Writing this book was difficult because the premises that we set out from were consistently challenged by the evidences before us."

They say that all writing in some way is auto/biography. What you select to write about, how you approach the subject, whose voices you highlight, all say something about you. Some would argue that the fact that we write individual biographies says something about our own psychologies too.

In the first decade of the 20th century in South Africa, when the two White nations, Brit and Boer, were not fighting each other they united in a common cause to trample those darker than themselves out of history. Gandhi, though, somehow muscled his way into a starring role. As bandy-legged as John Wayne, he shot sharp missives off to The Mercury, braved bullets on the battlefield at Spionkop, demanded guns to kill the uppity Natives, cajoled his community to carry the flag of Empire, took a beating from Indian thugs, supped with lower castes over fires and warmed-up beans and negotiated truces with Prime Ministers.

In between, Gandhi rested and experimented at his two ashrams, Phoenix and Tolstoy, while recruiting liberal-minded Whites to the Indian cause in South Africa.

One of the difficulties of following Gandhi is that he was careful to lay down a scent; a mere sniff of which may beguile the most erudite of trackers. You go along well-trodden paths, paths that show off Gandhi's political acumen and social grace. You go were your prey wants you to go.

What do I mean by this? Gandhi spent a long time tidying up his past in his autobiography, The Story of My Experiments with Truth. We all do that. But the art of writing biography is not to gobble up the given version and render it back to the reader. Much of what Gandhi himself later wrote about his sojourn was his own remembering and a large dose of forgetting.

We read and re-read all the relevant works of Gandhi, always mindful to cross reference his remembering to the actual writings at time of his actions. We looked at how he justified himself, and how his activities match that of the figure Gandhi has been represented to be during his South African years.

Writing this book was difficult because the premises that we set out from were consistently challenged by the evidences before us.

Some, on reading the blurbs announcing the book, have argued in pretty strong language, that we have sullied the name of Gandhi by exposing him as a unremitting man of Empire, a humanitarian who cared a jot about Africans -- asking for arms when they rebelled and more taxes to be imposed, an Aryan who single-mindedly committed himself to separating the Indian cause from the African one -- a man warning and cajoling those who worked alongside him in the Indian National Congress against the idea of Indo-African unity.

"The Gandhian pattern that emerges during the South African War and the Bhambatha Rebellion is the erasure of Africans as a people who suffered and resisted a brutal system."

We argue in our Gandhi that it is in fact those who have presented him as a cardboard cut-out figure that have sullied his image. We present a more rounded figure of the man.

The Gandhian pattern that emerges during the South African War and the Bhambatha Rebellion is the erasure of Africans as a people who suffered and resisted a brutal system. Alongside this was the use of war and violence as opportunities to display loyalty to local settlers and, by extension, to the British Empire. Ironically, on both occasions, Gandhi was on the side of those with the most fire-power. As if to reinforce this, in the aftermath of the Bhambatha Rebellion Gandhi called on the White authorities to allow an Indian militia to bear arms in defence of the racist colonial order.

The South African Gandhi cannot be defended on the basis that "India gave us a Mohandas, we gave them a Mahatma". What is needed in its place is a more sober version of his South African years.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![mahatma gandhi south africa]()

What writing Gandhi's biography showed us is that one cannot carefully select parts of history and expect, like many biographers of Gandhi, to get away with it. In fact, rather than helping your subject you expose the person to even greater and more critical scrutiny.

Today, in South Africa there are monuments of Gandhi, streets that bear his name, old iconic spots readying for a revamp to highlight his exploits. There is the occasional angry splotch of paint over a statue but this soon wears off.

This is how history works. Why let facts get in the way of a selling product?

Leaving Gandhi?

Following Gandhi around a century after he walked the same compromised streets that we do, was at first disenchanting. Like kids, we discovered that John Wayne was just, after all, an actor (a racist one to boot), no sidearm on his hip dispensing instant justice.

"Gandhi no longer represents some sort of high water mark in inter-racial cooperation in our land, a politics lost. No, Gandhi never was a saint, not even close."

The abiding lessons we learned are humility and aspiration. Humility at how difficult it is for a person, even with the best intentions, to escape their assigned position in society; how difficult it is to make any lasting mark on the forces of domination and exploitation is a society which, when under attack, divides, rules, reforms and co-opts. While Gandhi willingly offered the co-option of the community he represented in a bid to better its prospects, and did so in sometimes repugnant terms, we do recognise the overbearing strength of his opponent, a waning but still great Empire and a resurgent Boer nationalism.

This brings us to aspiration, because Gandhi no longer represents some sort of high water mark in inter-racial cooperation in our land, a politics lost. No, Gandhi never was a saint, not even close. Nor do many historical figures survive such close scrutiny. Some youngsters recently defaced Gandhi's statute in Johannesburg for his perceived racism, while others have demanded the defaming of Nelson Mandela, seen as a figure of excessive compromise who heralded disastrous economic policies. Truly, our own time in South Africa is marked with outrageous social and ecological developments that prideful social activists may one day be accused of unduly pandering to: African chauvinism, religious extremism, ecological depredation, an abiding anti-Blackness and the co-option of civil society, especially "radical" chic organisations that cannot wait to get the call from the government or Ford Foundation.

To see Gandhi clearly, strangely, allows the pursuit of all that is precious to Gandhism to resume with vigour: a just world changed through brave and persistent but non-violent, action.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() Like Us On Facebook |

Like Us On Facebook |

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() Follow Us On Twitter |

Follow Us On Twitter |

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() Contact HuffPost India

Contact HuffPost India

"[N]ot many people get to hurry up three flights of stairs to take tea with someone in the direct bloodline of a saint."

My mum told me very early on that the man who adorned the wall in our lounge was Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, Sita's grandfather. Every now and then she would provide little snippets of Gandhi's life. It was she who told me about Churchill's remark about the half-naked fakir: this after I begged her to dispense with her sari and wear a skirt like the white ladies walking down West Street. She told me about Gandhi pouring his tea into a saucer in some well-heeled London gathering and earning the scornful question of an aristocrat: "Why do you slurp from a saucer?" to which Gandhi replied, "So I can share the cup with you."

To a boy of 8, these stories, told at the height of apartheid's arrogance that forced us to live in narrower and narrower corners of the city, and where even the best parts of the nearby ocean were reserved for Whites, captivated and frustrated me. I drew pictures in my head of this mountain of a man whose every action, every utterance, constituted for my mother such a dominating moral landmark. Imagine the awe in visiting the Dhupelia's then, for not many people get to hurry up three flights of stairs to take tea with someone in the direct bloodline of a saint.

Down the road was the Raj Cinema. Here John Wayne held sway. The matinee show was jam-packed with youngsters. We screamed warnings to John Wayne when the bad guy with braids crept up behind him and clapped and danced when the last Indian was shot in the middle of the forehead.

John Wayne and Mohandas Gandhi. These were my heroes.

One day I asked my mother, "When will I meet this Gandhi?"

"You will Ashy boy, you will."

For seven years, on and off, Goolam Vahed and I have met Gandhi. In all kinds of places. In the archives. In journals and books. In newspapers and conferences. In monuments and street names.

"Writing this book was difficult because the premises that we set out from were consistently challenged by the evidences before us."

They say that all writing in some way is auto/biography. What you select to write about, how you approach the subject, whose voices you highlight, all say something about you. Some would argue that the fact that we write individual biographies says something about our own psychologies too.

In the first decade of the 20th century in South Africa, when the two White nations, Brit and Boer, were not fighting each other they united in a common cause to trample those darker than themselves out of history. Gandhi, though, somehow muscled his way into a starring role. As bandy-legged as John Wayne, he shot sharp missives off to The Mercury, braved bullets on the battlefield at Spionkop, demanded guns to kill the uppity Natives, cajoled his community to carry the flag of Empire, took a beating from Indian thugs, supped with lower castes over fires and warmed-up beans and negotiated truces with Prime Ministers.

In between, Gandhi rested and experimented at his two ashrams, Phoenix and Tolstoy, while recruiting liberal-minded Whites to the Indian cause in South Africa.

One of the difficulties of following Gandhi is that he was careful to lay down a scent; a mere sniff of which may beguile the most erudite of trackers. You go along well-trodden paths, paths that show off Gandhi's political acumen and social grace. You go were your prey wants you to go.

What do I mean by this? Gandhi spent a long time tidying up his past in his autobiography, The Story of My Experiments with Truth. We all do that. But the art of writing biography is not to gobble up the given version and render it back to the reader. Much of what Gandhi himself later wrote about his sojourn was his own remembering and a large dose of forgetting.

We read and re-read all the relevant works of Gandhi, always mindful to cross reference his remembering to the actual writings at time of his actions. We looked at how he justified himself, and how his activities match that of the figure Gandhi has been represented to be during his South African years.

Writing this book was difficult because the premises that we set out from were consistently challenged by the evidences before us.

Some, on reading the blurbs announcing the book, have argued in pretty strong language, that we have sullied the name of Gandhi by exposing him as a unremitting man of Empire, a humanitarian who cared a jot about Africans -- asking for arms when they rebelled and more taxes to be imposed, an Aryan who single-mindedly committed himself to separating the Indian cause from the African one -- a man warning and cajoling those who worked alongside him in the Indian National Congress against the idea of Indo-African unity.

"The Gandhian pattern that emerges during the South African War and the Bhambatha Rebellion is the erasure of Africans as a people who suffered and resisted a brutal system."

We argue in our Gandhi that it is in fact those who have presented him as a cardboard cut-out figure that have sullied his image. We present a more rounded figure of the man.

The Gandhian pattern that emerges during the South African War and the Bhambatha Rebellion is the erasure of Africans as a people who suffered and resisted a brutal system. Alongside this was the use of war and violence as opportunities to display loyalty to local settlers and, by extension, to the British Empire. Ironically, on both occasions, Gandhi was on the side of those with the most fire-power. As if to reinforce this, in the aftermath of the Bhambatha Rebellion Gandhi called on the White authorities to allow an Indian militia to bear arms in defence of the racist colonial order.

The South African Gandhi cannot be defended on the basis that "India gave us a Mohandas, we gave them a Mahatma". What is needed in its place is a more sober version of his South African years.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

What writing Gandhi's biography showed us is that one cannot carefully select parts of history and expect, like many biographers of Gandhi, to get away with it. In fact, rather than helping your subject you expose the person to even greater and more critical scrutiny.

Today, in South Africa there are monuments of Gandhi, streets that bear his name, old iconic spots readying for a revamp to highlight his exploits. There is the occasional angry splotch of paint over a statue but this soon wears off.

This is how history works. Why let facts get in the way of a selling product?

Leaving Gandhi?

Following Gandhi around a century after he walked the same compromised streets that we do, was at first disenchanting. Like kids, we discovered that John Wayne was just, after all, an actor (a racist one to boot), no sidearm on his hip dispensing instant justice.

"Gandhi no longer represents some sort of high water mark in inter-racial cooperation in our land, a politics lost. No, Gandhi never was a saint, not even close."

The abiding lessons we learned are humility and aspiration. Humility at how difficult it is for a person, even with the best intentions, to escape their assigned position in society; how difficult it is to make any lasting mark on the forces of domination and exploitation is a society which, when under attack, divides, rules, reforms and co-opts. While Gandhi willingly offered the co-option of the community he represented in a bid to better its prospects, and did so in sometimes repugnant terms, we do recognise the overbearing strength of his opponent, a waning but still great Empire and a resurgent Boer nationalism.

This brings us to aspiration, because Gandhi no longer represents some sort of high water mark in inter-racial cooperation in our land, a politics lost. No, Gandhi never was a saint, not even close. Nor do many historical figures survive such close scrutiny. Some youngsters recently defaced Gandhi's statute in Johannesburg for his perceived racism, while others have demanded the defaming of Nelson Mandela, seen as a figure of excessive compromise who heralded disastrous economic policies. Truly, our own time in South Africa is marked with outrageous social and ecological developments that prideful social activists may one day be accused of unduly pandering to: African chauvinism, religious extremism, ecological depredation, an abiding anti-Blackness and the co-option of civil society, especially "radical" chic organisations that cannot wait to get the call from the government or Ford Foundation.

To see Gandhi clearly, strangely, allows the pursuit of all that is precious to Gandhism to resume with vigour: a just world changed through brave and persistent but non-violent, action.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Like Us On Facebook |

Like Us On Facebook | Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Follow Us On Twitter |

Follow Us On Twitter | Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.