It was a set drill. A midnight knock followed by an arrest and then a transfer to prison. The Emergency had arrived, and India was no longer a free nation that upheld rule of law.

On 25 June 1975, then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi imposed internal emergency and became the country's de facto dictator. India was told that the leader was right and our future was bright. Bright for whom? The thousands who ended up incarcerated and detained with little prospect of release? For a nation that faced a future of systematic torture, subversion of democratic institutions, corruption and curtailed freedom of expression?

![noted socialist leader raj narain in center]()

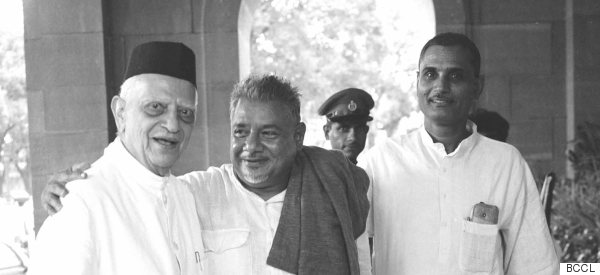

It was the election petition by Raj Narain (centre) that set into motion events that culminated in the emergency.

A perfect storm

Many of today's commentariat develop cold feet when it comes to identifying Mrs Indira Gandhi's role. A bureaucrat here or an advisor there gets blamed for having misled the iron lady of India into promulgating emergency. Then there are those who, simplistically, pin the reason for the Emergency on the Raj Narain case, in which the Allahabad High Court upheld charges of electoral misdoing against Mrs Gandhi and set aside her election as an MP. However, none of these even scratch the surface to reveal the full scale of factors that built up to the Emergency.

"Many of today's commentariat develop cold feet when it comes to identifying Mrs Indira Gandhi's role."

Indian polity entered an uncertain phase after the death of Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri in January 1966. The Indian National Congress was a colossal ship that was ready to be commandeered by a new captain. Someone was to inherit the gigantic goodwill and groundswell of support that existed for the INC. It seemed Indira Gandhi was the least likely person to pull off a clean victory in opposition to the "Syndicate". However it did happen and for a little while it seemed that the former "Goongi Gudiya" (dumb doll) had emerged the winner. But new clouds were looming on the horizon -- the state assembly elections of 1967 saw simultaneous defeats of provincial INC governments. Although the victors belonged to different ends of the political spectrum, the idea that the INC was electorally invincible started to dissolve.

In addition to the internal political upheaval in the late 60s, geopolitically too a great game was in the offing. The US was beginning to make a mess of its Asia policy by getting involved in a ground war in Vietnam and simultaneously pursuing a policy of "tilt" towards Pakistan. The US presence in the near neighbourhood on both Eastern and Western flanks saw Mrs. Gandhi deftly execute a treaty with the Soviet Union. With this treaty Soviet influence reached its zenith in the country -- India nationalised its banks, insurance companies and other large swathes of the economy in its efforts to ally with Soviet Union. However, the Indo-Soviet treaty was to come handy in 1971.

All of these moves on the global and national political chessboards culminated in the Bangladesh liberation war of 1971. A victory in the war catapulted the stature of Mrs. Gandhi to a new high. She became the toast of the nation and was even hailed as "Maa Durga" in Parliament by opposition leader and future prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee. With Pakistan cut to size, immense support within the country and a global stature to boot, it seemed nothing could go wrong for Mrs Indira Gandhi. But she had an Achilles Heel - a paranoia of being deposed coupled with a hunger for centralisation of power. Her tendency for autocratic policy changes and rule by fiat were becoming more and more apparent by 1972.

![nanaji deshmukh]()

Nanaji Deshmukh was a major opposition figure during the emergency.

This change of attitude did not escape the notice of a select band of thinkers and leaders who came from diverse backgrounds but were united in their struggle to save Indian democracy. Ram Nath Goenka of The Indian Express, Nanaji Deshmukh of the RSS and Hindi poet laureate Ramdhari Singh Dinkar were among them. This motley group had resolution, media reach, dedicated cadres and the intellect to take on the Prime Minister. But they lacked one crucial element -- a leader. Without someone to lead the anti-Congress sentiment to action, their hands were tied.

"I was about three when the mayhem started, and by seven I was already an adult."

This is where Nanaji, a master strategist, pulled off challenging political calisthenics and persuaded Jai Prakash Narain or JP to lead the movement upfront. Unnerved by a rising political groundswell and a tanked economy that made shortages and unemployment rampant, Mrs Indira Gandhi had every reason to be spooked. Fearing political defeat, she did the only thing she could to preserve her power: declare Emergency.

A childhood in hiding

On 25 June this year, I wrote some random tweets on Emergency. Rana Safvi asked me how old I was during emergency. I replied "I was about three when the mayhem started, and by seven I was already an adult."

In 1976, I was too young to comprehend death, but as a toddler I witnessed the body of an opposition activist being handed over to his mother as she wailed and cursed Indira Gandhi.

The Emergency was the closest India came towards being a Stalinist state. My father Yadav Rao Deshmukh was editor of RSS mouthpiece Panchjanya and my uncles and other family members were RSS luminaries including Keshav Rao Deshmukh and Madhav Rao Deshmukh, apart from Nanaji Deshmukh who was hands-on involved in the JP movement as the Jan Sangh mastermind. He and his closest friend RNG (Ram Nath Goenka) were instrumental in pulling JP out of inertia and pushing him back in his untiring freedom-fighting mode. Together, they structured what was known as "Sampoorn Kranti Movement" or simply "JP Andolan".

Such close association with the "organised opposition" meant only one thing, overnight my family was considered enemy of the state. One by one my family members were either arrested or went in hiding. As soon as Emergency was imposed, my father went underground in disguise.

The state machinery was instructed to get hold of opposition leaders and activists by all means possible. To ensure my father's freedom my mother also had to be constantly on the run. She knew that if the police got their hands on her, they might be able to blackmail Baba into surrendering. With me in tow, she'd flit from place to place, never resting her feet for more than a couple of hours. Many times she sought refuge in Santoshi Mata Mandir in Ganeshganj, Lucknow.

"To ensure my father's freedom my mother also had to be constantly on the run. She knew that if the police got their hands on her, they might be able to blackmail Baba into surrendering."

My parent's defiance came at a personal price. Frustrated upon not finding us, the "unknown mob" as Sanjay Gandhi's hooligans were vaguely referred to by officials, raided our house in Lucknow and looted whatever little we had. What they didn't loot, they burned in our courtyard - furniture, clothes, books, all my toys. Much later, as I looked at that black mass that our belongings were reduced to, I felt nothing. I still feel that strange numbness whenever I look at photographs of similar things anywhere in the world.

I did not get any more toys throughout my childhood and almost 20 years later when I earned my first salary, I bought a big teddy for myself. I still don't know exactly what compelled me to do that. I remember my mother cried for a long time when she saw that teddy bear. Perhaps she was mourning my childhood, incinerated as it was in the pyre of Emergency.

As for my father, his luck ran out as well.

A dedicated RSS pracharak, he wore a dhoti-kurta until the last days of his life but during the initial months of Emergency he took to wearing a three piece suit and carried a pack of cigarettes in his pocket. He became anything and everything that did not define him, to resist. He was an organisation man par excellence and one of the most sought after "anti-government" individuals. But in one of the usual stop-and-search exercises, a postcard was found on his person with the address of "42 Arya Nagar, Lucknow". This particular address was under police surveillance, as many opposition and media dissenters -- including Achyutanand Mishra and Prof Devendra Swaroop -- had lived there under the protection of a pious Gujarati family. Some further questioning followed. When a person who was accompanying him ran away, the police's suspicions were aroused and they detained my father.

It was a matter of time before they identified and sent a proud message to their superiors - "Humne to machhli pakadne ke liye jaal bichhaya tha, aur magarmach pakda gaya" (we had cast our net to catch small fish but instead netted a big crocodile)! In a way, Baba's arrest was a big personal relief for us as now we wouldn't have to be on the run constantly.

After Baba's arrest, the scene of action for my family shifted back to Benares. Our home became the centre of Andolan sympathisers. Manning the underground communication network and the clandestine organization was my aunt, Mrs Sarojini Deshmukh, the matron of BHU Medical College Hospital. She was fondly known as Durga Bhabhi or Durga Kaku by all - to me she was Aai.

"Many times, I'd hide correspondence between opposition leaders in my chaddis and smuggle the letters in and out of jail."

She was the principal point of contact for families of leaders in jails, as well as sympathisers in UP and Bihar. She saw to the medical needs of all jailed Opposition leaders, regardless of their ideological affiliations. She also ensured material relief for families whose primary breadwinners were in jails and also organised medical aid for underground activists who visited BHU medical college. I used to accompany her for all her jail visits. It was how we spent all our weekends.

She was a source of succour for tortured activists. I remember how a young activist, who probably did not cry that much when his finger nails were pulled off during police interrogation, sobbed inconsolably while looking upon Aai as she dressed his wounds. We visited Naini Jail, Tihar Jail, Lucknow Jail and few more by rotation. My father was lodged in Lucknow Jail and his number to meet would only come up once every two months or so by rotation. The visitor stamp of the jails was too big for my tiny wrists, so my palm would be stamped instead.

Apart from the medical supervision, Aai was leading a truly world-class underground communication network and I was perhaps its youngest courier. Many times, I'd hide correspondence between opposition leaders in my chaddis and smuggle the letters in and out of jail. All I knew was that I must stay quiet as I held on to Aai's finger as we walked in or out of prison gates.

My role came with benefits, and I was treated like a little celebrity by friends of my father and uncles. I think I helped them forget their stress for a while. I used to love visiting them though my heart would be wrenched every time I left them behind. I'd fall into a depressed silence as we went home, clutching on to Aai for comfort like the five-year-old I was.

The story of Emergency was not one of merely the opposition leaders and activists. The Emergency was also a story of ordinary men and women who had no ideological predilections but chose to do what was right rather than what was convenient.

Doctors and nurses at Banaras Hindu University Medical College treated underground resistance members, undertaking grave personal risk at the hands of a brutal state machinery. In Lucknow, our neighbours - the De, Sawant and Nabi families -- provided an emotional anchor in an atmosphere of all pervasive misery. I vividly recall Nanijan (mother of Athar and Azhar Nabi) giving a tongue lashing to the police personnel deputed for surveillance at our looted and gutted Lucknow house. Lawyer Mr Gupta offered to save our house from government resumption by arranging transfer of same. Dr. Dubey of Lucknow medical college went out of his way to help my parents when they were ill at the same time. He got both my parents shifted to hospital at Tudiyaganj -- my father from from Lucknow Jail and my mother from BHU medical college. This was our first family reunion in a year with both of my parents on hospital bed and I sitting on a stool in between. This happiness lasted for only a week until my father was sent back to jail again.

The emergency was characterised by another peculiar feature. The RSS and its affiliate network became the backbone of resistance for all political parties. It became a communications hub, logistics camp and human resource pool for Socialists, regional outfits, former Congressmen and activists alike. Unlike the RSS the Socialist leadership did not have the benefit of deep and entrenched familial networks of cadres. The deeply rooted organisation and network not only validated itself during the test of Emergency, it served opposition politicians of all hues without fear or favour. Instead of destroying the organisation, the Emergency firmly established the RSS as the lead unit in the opposition. A status that in future allowed it to nurture the BJP into a formidable electoral machinery.

"'Election' as a word became imprinted in my psyche. For me it was like a magic wand that was supposed to remove the all-pervasive misery. And it did not disappoint."

The winter of 1976 brought new ray of hope, there was talk of elections in the air. Although my schooling had started at Malviya Shishu Vihar in BHU, I did not quite grasp the import of this. However, the prospect of my family, friends and acquaintances being released was indeed a great thing! "Election" as a word became imprinted in my psyche. For me it was like a magic wand that was supposed to remove the all-pervasive misery. And it did not disappoint.

Despite the announcement of elections in 1977, a lot of leaders were still in the prisons and there was no guarantee that Mrs Gandhi would lose. My cousins used to go out at midnight and paint Pro-Andolan graffiti which was not the most discreet thing to do given that so many family members were still in jail. On the eventful results night I was sound asleep in Aai's lap and India was glued to All India Radio -- the only outlet broadcasting live results. AIR announced way past midnight that Mrs Gandhi had lost her seat from Rae Bareilly.

![indira gandhi_emergency 1975]()

Former Prime Minister Mrs Indira Gandhi (in saree) along with Sanjay Gandhi (left in shawl) appears before Shah Commission, inquiring excesses done during Emergency, in New Delhi on January 29, 1978.

Freedom at last

My cousins would repeat the dramatic lines many times over in the coming days, trying to mimic the deep voice and gravitas of the newscaster:"Rae Bareilly Sansadiya kshetra se Pradhanmantri Shrimati Indira Gandhi apne nikat-tam pratidwandi Raj Narain se 50000 se bhi jyada maton se......(then a long pause)...HAAR gayin hai (From the constituency of Rae Bareilly, with a margin of 50000 votes against Raj Narain, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi has... LOST)."

Apparently there were few moments of silent disbelief before cheers and shouts of joy broke out across the neighbourhood. I woke up to celebrations and revelry quite alien to the past two years. Finally our ordeal and those of thousands of other families were over. The battle for ideals of India had been settled and a resolute band of individuals had bested an autocratic leader who wielded state power. The Emergency was over and now was the time to limp back to normalcy and rebuild the nation.

"When Mrs Gandhi was assassinated in 1984, I drew a portrait of her at my school and my father asked me to caption it 'The Torch Bearer'."

I can never forget the enthusiasm all around when the opposition leaders were released from jail. Madhav Kaka and Aai were taken home from the station on a rickshaw pulled by scores of karykartas. All along the way people were showering flowers and petals from the balconies and rooftops. Sandwiched between Kaka and Aai, I was both amused and elated. There were so many happy faces all around. For me, it was a welcome change.

Soon after, I returned to Lucknow with my parents. To pick up where we left off was not easy. Four sets of plates, some glasses, a katori, a pressure cooker and a kerosene stove were all that remained in our Lucknow home that July of 1977. Baba being himself had refused to apply for any compensation for the damages. For him there were many other families that had suffered much more than us and they deserved priority. Ma stood rock solid behind his every decision. For years to come, khichdi remained our favourite staple food, offered equally to scores of DRI workers who were a permanent fixture in our household. To me nothing mattered more than being with my parents under one roof, which even though still black from the fumes of the bonfire of 1976 was still our own.

Despite the harassment and ill-treatment meted out to the opposition I was never taught to be bitter about my experiences. When Mrs Gandhi was assassinated in 1984, I drew a portrait of her at my school and my father asked me to caption it "The Torch Bearer". He made it a point, along with my uncle, to pay tribute at her funeral. Despite their ideological differences and a history of bad blood Baba could still carry out an objective assessment of her leadership qualities and the other good things that she could do for India. I am proud to inherit such values and the ability to forgive and see the positives. The Emergency was bigger than the sum of personal experiences and stories. It was a struggle for democratic principles and one that enriched Indian polity for decades to come.

![]() Like Us On Facebook |

Like Us On Facebook |

![]() Follow Us On Twitter |

Follow Us On Twitter |

![]() Contact HuffPost India

Contact HuffPost India

On 25 June 1975, then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi imposed internal emergency and became the country's de facto dictator. India was told that the leader was right and our future was bright. Bright for whom? The thousands who ended up incarcerated and detained with little prospect of release? For a nation that faced a future of systematic torture, subversion of democratic institutions, corruption and curtailed freedom of expression?

It was the election petition by Raj Narain (centre) that set into motion events that culminated in the emergency.

A perfect storm

Many of today's commentariat develop cold feet when it comes to identifying Mrs Indira Gandhi's role. A bureaucrat here or an advisor there gets blamed for having misled the iron lady of India into promulgating emergency. Then there are those who, simplistically, pin the reason for the Emergency on the Raj Narain case, in which the Allahabad High Court upheld charges of electoral misdoing against Mrs Gandhi and set aside her election as an MP. However, none of these even scratch the surface to reveal the full scale of factors that built up to the Emergency.

"Many of today's commentariat develop cold feet when it comes to identifying Mrs Indira Gandhi's role."

Indian polity entered an uncertain phase after the death of Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri in January 1966. The Indian National Congress was a colossal ship that was ready to be commandeered by a new captain. Someone was to inherit the gigantic goodwill and groundswell of support that existed for the INC. It seemed Indira Gandhi was the least likely person to pull off a clean victory in opposition to the "Syndicate". However it did happen and for a little while it seemed that the former "Goongi Gudiya" (dumb doll) had emerged the winner. But new clouds were looming on the horizon -- the state assembly elections of 1967 saw simultaneous defeats of provincial INC governments. Although the victors belonged to different ends of the political spectrum, the idea that the INC was electorally invincible started to dissolve.

In addition to the internal political upheaval in the late 60s, geopolitically too a great game was in the offing. The US was beginning to make a mess of its Asia policy by getting involved in a ground war in Vietnam and simultaneously pursuing a policy of "tilt" towards Pakistan. The US presence in the near neighbourhood on both Eastern and Western flanks saw Mrs. Gandhi deftly execute a treaty with the Soviet Union. With this treaty Soviet influence reached its zenith in the country -- India nationalised its banks, insurance companies and other large swathes of the economy in its efforts to ally with Soviet Union. However, the Indo-Soviet treaty was to come handy in 1971.

All of these moves on the global and national political chessboards culminated in the Bangladesh liberation war of 1971. A victory in the war catapulted the stature of Mrs. Gandhi to a new high. She became the toast of the nation and was even hailed as "Maa Durga" in Parliament by opposition leader and future prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee. With Pakistan cut to size, immense support within the country and a global stature to boot, it seemed nothing could go wrong for Mrs Indira Gandhi. But she had an Achilles Heel - a paranoia of being deposed coupled with a hunger for centralisation of power. Her tendency for autocratic policy changes and rule by fiat were becoming more and more apparent by 1972.

Nanaji Deshmukh was a major opposition figure during the emergency.

This change of attitude did not escape the notice of a select band of thinkers and leaders who came from diverse backgrounds but were united in their struggle to save Indian democracy. Ram Nath Goenka of The Indian Express, Nanaji Deshmukh of the RSS and Hindi poet laureate Ramdhari Singh Dinkar were among them. This motley group had resolution, media reach, dedicated cadres and the intellect to take on the Prime Minister. But they lacked one crucial element -- a leader. Without someone to lead the anti-Congress sentiment to action, their hands were tied.

"I was about three when the mayhem started, and by seven I was already an adult."

This is where Nanaji, a master strategist, pulled off challenging political calisthenics and persuaded Jai Prakash Narain or JP to lead the movement upfront. Unnerved by a rising political groundswell and a tanked economy that made shortages and unemployment rampant, Mrs Indira Gandhi had every reason to be spooked. Fearing political defeat, she did the only thing she could to preserve her power: declare Emergency.

A childhood in hiding

On 25 June this year, I wrote some random tweets on Emergency. Rana Safvi asked me how old I was during emergency. I replied "I was about three when the mayhem started, and by seven I was already an adult."

In 1976, I was too young to comprehend death, but as a toddler I witnessed the body of an opposition activist being handed over to his mother as she wailed and cursed Indira Gandhi.

The Emergency was the closest India came towards being a Stalinist state. My father Yadav Rao Deshmukh was editor of RSS mouthpiece Panchjanya and my uncles and other family members were RSS luminaries including Keshav Rao Deshmukh and Madhav Rao Deshmukh, apart from Nanaji Deshmukh who was hands-on involved in the JP movement as the Jan Sangh mastermind. He and his closest friend RNG (Ram Nath Goenka) were instrumental in pulling JP out of inertia and pushing him back in his untiring freedom-fighting mode. Together, they structured what was known as "Sampoorn Kranti Movement" or simply "JP Andolan".

Such close association with the "organised opposition" meant only one thing, overnight my family was considered enemy of the state. One by one my family members were either arrested or went in hiding. As soon as Emergency was imposed, my father went underground in disguise.

The state machinery was instructed to get hold of opposition leaders and activists by all means possible. To ensure my father's freedom my mother also had to be constantly on the run. She knew that if the police got their hands on her, they might be able to blackmail Baba into surrendering. With me in tow, she'd flit from place to place, never resting her feet for more than a couple of hours. Many times she sought refuge in Santoshi Mata Mandir in Ganeshganj, Lucknow.

"To ensure my father's freedom my mother also had to be constantly on the run. She knew that if the police got their hands on her, they might be able to blackmail Baba into surrendering."

My parent's defiance came at a personal price. Frustrated upon not finding us, the "unknown mob" as Sanjay Gandhi's hooligans were vaguely referred to by officials, raided our house in Lucknow and looted whatever little we had. What they didn't loot, they burned in our courtyard - furniture, clothes, books, all my toys. Much later, as I looked at that black mass that our belongings were reduced to, I felt nothing. I still feel that strange numbness whenever I look at photographs of similar things anywhere in the world.

I did not get any more toys throughout my childhood and almost 20 years later when I earned my first salary, I bought a big teddy for myself. I still don't know exactly what compelled me to do that. I remember my mother cried for a long time when she saw that teddy bear. Perhaps she was mourning my childhood, incinerated as it was in the pyre of Emergency.

As for my father, his luck ran out as well.

A dedicated RSS pracharak, he wore a dhoti-kurta until the last days of his life but during the initial months of Emergency he took to wearing a three piece suit and carried a pack of cigarettes in his pocket. He became anything and everything that did not define him, to resist. He was an organisation man par excellence and one of the most sought after "anti-government" individuals. But in one of the usual stop-and-search exercises, a postcard was found on his person with the address of "42 Arya Nagar, Lucknow". This particular address was under police surveillance, as many opposition and media dissenters -- including Achyutanand Mishra and Prof Devendra Swaroop -- had lived there under the protection of a pious Gujarati family. Some further questioning followed. When a person who was accompanying him ran away, the police's suspicions were aroused and they detained my father.

It was a matter of time before they identified and sent a proud message to their superiors - "Humne to machhli pakadne ke liye jaal bichhaya tha, aur magarmach pakda gaya" (we had cast our net to catch small fish but instead netted a big crocodile)! In a way, Baba's arrest was a big personal relief for us as now we wouldn't have to be on the run constantly.

After Baba's arrest, the scene of action for my family shifted back to Benares. Our home became the centre of Andolan sympathisers. Manning the underground communication network and the clandestine organization was my aunt, Mrs Sarojini Deshmukh, the matron of BHU Medical College Hospital. She was fondly known as Durga Bhabhi or Durga Kaku by all - to me she was Aai.

"Many times, I'd hide correspondence between opposition leaders in my chaddis and smuggle the letters in and out of jail."

She was the principal point of contact for families of leaders in jails, as well as sympathisers in UP and Bihar. She saw to the medical needs of all jailed Opposition leaders, regardless of their ideological affiliations. She also ensured material relief for families whose primary breadwinners were in jails and also organised medical aid for underground activists who visited BHU medical college. I used to accompany her for all her jail visits. It was how we spent all our weekends.

She was a source of succour for tortured activists. I remember how a young activist, who probably did not cry that much when his finger nails were pulled off during police interrogation, sobbed inconsolably while looking upon Aai as she dressed his wounds. We visited Naini Jail, Tihar Jail, Lucknow Jail and few more by rotation. My father was lodged in Lucknow Jail and his number to meet would only come up once every two months or so by rotation. The visitor stamp of the jails was too big for my tiny wrists, so my palm would be stamped instead.

Apart from the medical supervision, Aai was leading a truly world-class underground communication network and I was perhaps its youngest courier. Many times, I'd hide correspondence between opposition leaders in my chaddis and smuggle the letters in and out of jail. All I knew was that I must stay quiet as I held on to Aai's finger as we walked in or out of prison gates.

My role came with benefits, and I was treated like a little celebrity by friends of my father and uncles. I think I helped them forget their stress for a while. I used to love visiting them though my heart would be wrenched every time I left them behind. I'd fall into a depressed silence as we went home, clutching on to Aai for comfort like the five-year-old I was.

The story of Emergency was not one of merely the opposition leaders and activists. The Emergency was also a story of ordinary men and women who had no ideological predilections but chose to do what was right rather than what was convenient.

Doctors and nurses at Banaras Hindu University Medical College treated underground resistance members, undertaking grave personal risk at the hands of a brutal state machinery. In Lucknow, our neighbours - the De, Sawant and Nabi families -- provided an emotional anchor in an atmosphere of all pervasive misery. I vividly recall Nanijan (mother of Athar and Azhar Nabi) giving a tongue lashing to the police personnel deputed for surveillance at our looted and gutted Lucknow house. Lawyer Mr Gupta offered to save our house from government resumption by arranging transfer of same. Dr. Dubey of Lucknow medical college went out of his way to help my parents when they were ill at the same time. He got both my parents shifted to hospital at Tudiyaganj -- my father from from Lucknow Jail and my mother from BHU medical college. This was our first family reunion in a year with both of my parents on hospital bed and I sitting on a stool in between. This happiness lasted for only a week until my father was sent back to jail again.

The emergency was characterised by another peculiar feature. The RSS and its affiliate network became the backbone of resistance for all political parties. It became a communications hub, logistics camp and human resource pool for Socialists, regional outfits, former Congressmen and activists alike. Unlike the RSS the Socialist leadership did not have the benefit of deep and entrenched familial networks of cadres. The deeply rooted organisation and network not only validated itself during the test of Emergency, it served opposition politicians of all hues without fear or favour. Instead of destroying the organisation, the Emergency firmly established the RSS as the lead unit in the opposition. A status that in future allowed it to nurture the BJP into a formidable electoral machinery.

"'Election' as a word became imprinted in my psyche. For me it was like a magic wand that was supposed to remove the all-pervasive misery. And it did not disappoint."

The winter of 1976 brought new ray of hope, there was talk of elections in the air. Although my schooling had started at Malviya Shishu Vihar in BHU, I did not quite grasp the import of this. However, the prospect of my family, friends and acquaintances being released was indeed a great thing! "Election" as a word became imprinted in my psyche. For me it was like a magic wand that was supposed to remove the all-pervasive misery. And it did not disappoint.

Despite the announcement of elections in 1977, a lot of leaders were still in the prisons and there was no guarantee that Mrs Gandhi would lose. My cousins used to go out at midnight and paint Pro-Andolan graffiti which was not the most discreet thing to do given that so many family members were still in jail. On the eventful results night I was sound asleep in Aai's lap and India was glued to All India Radio -- the only outlet broadcasting live results. AIR announced way past midnight that Mrs Gandhi had lost her seat from Rae Bareilly.

Former Prime Minister Mrs Indira Gandhi (in saree) along with Sanjay Gandhi (left in shawl) appears before Shah Commission, inquiring excesses done during Emergency, in New Delhi on January 29, 1978.

Freedom at last

My cousins would repeat the dramatic lines many times over in the coming days, trying to mimic the deep voice and gravitas of the newscaster:"Rae Bareilly Sansadiya kshetra se Pradhanmantri Shrimati Indira Gandhi apne nikat-tam pratidwandi Raj Narain se 50000 se bhi jyada maton se......(then a long pause)...HAAR gayin hai (From the constituency of Rae Bareilly, with a margin of 50000 votes against Raj Narain, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi has... LOST)."

Apparently there were few moments of silent disbelief before cheers and shouts of joy broke out across the neighbourhood. I woke up to celebrations and revelry quite alien to the past two years. Finally our ordeal and those of thousands of other families were over. The battle for ideals of India had been settled and a resolute band of individuals had bested an autocratic leader who wielded state power. The Emergency was over and now was the time to limp back to normalcy and rebuild the nation.

"When Mrs Gandhi was assassinated in 1984, I drew a portrait of her at my school and my father asked me to caption it 'The Torch Bearer'."

I can never forget the enthusiasm all around when the opposition leaders were released from jail. Madhav Kaka and Aai were taken home from the station on a rickshaw pulled by scores of karykartas. All along the way people were showering flowers and petals from the balconies and rooftops. Sandwiched between Kaka and Aai, I was both amused and elated. There were so many happy faces all around. For me, it was a welcome change.

Soon after, I returned to Lucknow with my parents. To pick up where we left off was not easy. Four sets of plates, some glasses, a katori, a pressure cooker and a kerosene stove were all that remained in our Lucknow home that July of 1977. Baba being himself had refused to apply for any compensation for the damages. For him there were many other families that had suffered much more than us and they deserved priority. Ma stood rock solid behind his every decision. For years to come, khichdi remained our favourite staple food, offered equally to scores of DRI workers who were a permanent fixture in our household. To me nothing mattered more than being with my parents under one roof, which even though still black from the fumes of the bonfire of 1976 was still our own.

Despite the harassment and ill-treatment meted out to the opposition I was never taught to be bitter about my experiences. When Mrs Gandhi was assassinated in 1984, I drew a portrait of her at my school and my father asked me to caption it "The Torch Bearer". He made it a point, along with my uncle, to pay tribute at her funeral. Despite their ideological differences and a history of bad blood Baba could still carry out an objective assessment of her leadership qualities and the other good things that she could do for India. I am proud to inherit such values and the ability to forgive and see the positives. The Emergency was bigger than the sum of personal experiences and stories. It was a struggle for democratic principles and one that enriched Indian polity for decades to come.

Like Us On Facebook |

Like Us On Facebook |  Follow Us On Twitter |

Follow Us On Twitter |